This summer, I have the opportunity to conduct research at Concordia University, generously funded by NSERC. While pursuing my Computer Science degree, I’ve come to realize that my knowledge and technical experience in the realm of robotics and electronics are somewhat limited. This is unfortunate since my interests lie in these fields. I firmly believe that achieving artificial general intelligence requires a focus on embedded systems and intelligent hardware, rather than solely relying on large language models and software-interface only models. While software and the internet provide a constant stream of data, they remain disconnected from the reality we humans experience. To truly attain intelligence, a system must possess the ability to perceive, sense, and interpret its surroundings. This can only be accomplished through the integration of both hardware and software, rather than relying solely on software models. Moreover, designing these hardware models to resemble humans can lead to intelligent systems that generate solutions relevant to our own needs.

It is truly fascinating and exciting to witness the emergence of these discussions. The conversations and terminology used bear resemblance to the readings of scripture and the creation of life. Ethical, philosophical, and technological questions intertwine, as the development of truly intelligent systems transcends the realm of technology. The design choices we make, the limitations we impose, and the advantages we provide lie entirely within our hands, but necessitate multi-domain thinking to ensure we get it right.

Embarking on a Project

Moving beyond contemplation, I was motivated to embark on a project that delves deeper into these ideas. In my search for open-source robot specifications, I stumbled upon this Hexapod repository that seemed perfect. The Hexapod’s size, cost-effectiveness, relative ease of balancing compared to quadrupeds or bipeds, and the ability to customize its features according to my preferences all appealed to me. My goal is to explore how embedded intelligent systems react and learn within the constraints of a body structure, emulating the similarity to all living creatures on Earth.

3D Modelling and Slicing

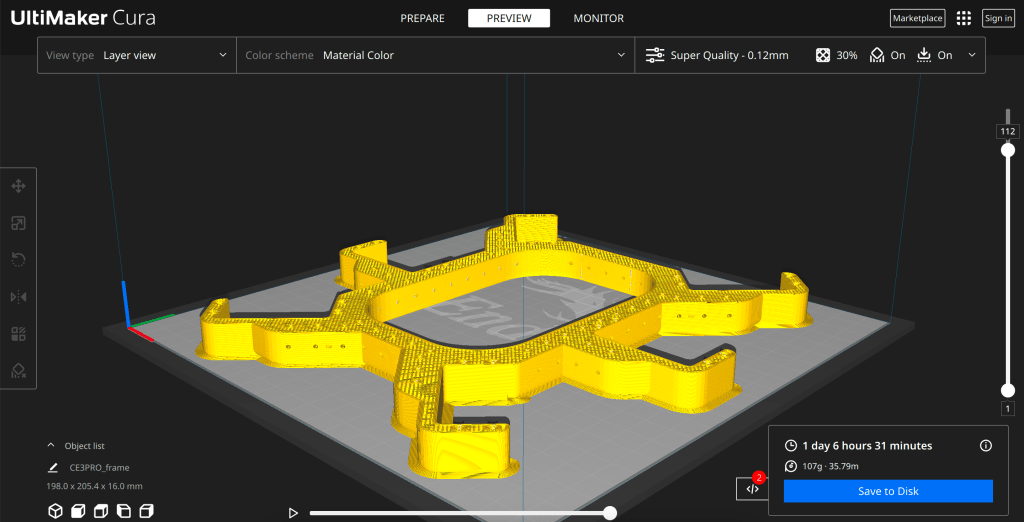

To kickstart this project, the first step involved downloading the 3D models and processing them through slicing software called Ultimaker Cura. A slicing software takes a 3D model and “slices” it into a set of layered instructions that the 3D printer can understand. Additionally, Cura provides extensive customization options to influence print quality, such as adjusting the layer height, hotbed temperature, filament density, and more. Here, precision and fine-tuning become paramount in achieving optimal results.

Figure 1: Hexapod frame in Ultimaker Cura slicing software

Filaments and Printers

The next step entailed selecting the appropriate filament and printers for the project. Opting for standard PLA plastic, a commonly used and beginner-friendly material in 3D printing, I aimed for accessibility and ease of use. As for the printers, the primary one employed during the printing process was a modified Creality Ender 3 Pro, accompanied by a Prusa Mark III and a Raise3D Pro2. Each printer possesses its own set of advantages and disadvantages, demanding careful calibration to achieve high-quality prints.

Figure 2: My modified Ender 3 Pro 3D printer

Post-Processing PLA Prints

To achieve a standardized color and enhance the visual aesthetics of the PLA prints, a meticulous post-processing routine was executed. The raw printed parts exhibit visible layer lines, which are not visually pleasing. The step-by-step process for each part involved:

- Sanding with 120-grit paper

- Subsequent sanding with 210-grit paper

- Further refinement using 340-grit paper

- Thorough washing

- Application of sandable filler by spraying

- Sanding with 400-grit paper

- Another washing session

- Spot Putty application

- Sanding once again with 400-grit paper

- Washing

- Final application of sandable filler by spraying

- Wet sanding with 600-grit paper

- Final wet sanding with 1200-grit paper

After completing the post-processing stage, the parts were ready for painting. This step proved relatively simpler, involving the application of a ground coat followed by an anodized dark grey chrome finish. The “skeleton” of the robot would assume this colour, while the accent and protective pieces would retain their matte blue plastic appearance, remaining unprocessed and unfinished.

Figure 3: Processed and painted parts vs raw PLA plastic

Stay Tuned for More

This concludes the first part of this multipart series. I invite you to stay updated on the progress of this project by signing up for my newsletter or following me on LinkedIn. In future installments, we will delve deeper into the development of the Hexapod and explore its integration with intelligent systems and software models. Together, let’s unravel the fascinating journey toward achieving true intelligence through the fusion of hardware and software.

Leave a comment